On May 12, 2025, the head of the U.S. Department of Justice Criminal Division, Matthew Galeotti, announced a new white-collar enforcement plan rooted in three tenets: “focus, fairness, and efficiency.” The new plan includes updates to the Criminal

Division’s Corporate Enforcement Policy, independent compliance monitor selection policy, and whistleblower programs.

In announcing the new plan, Galeotti explained that the DOJ’s Criminal Division “is turning a new page on white-collar and

corporate enforcement,” and despite recent indications of a step back from corporate criminal enforcement by the DOJ, the

plan suggests that such enforcement is certain to continue in many ways that are familiar to companies and counsel. The

plan designates 10 areas of focus for white-collar enforcement: Some are longstanding enforcement priorities, such as health

care fraud, and some are newer initiatives that align with the Trump Administration’s priorities, such as trade and tariff-related enforcement.

Ten Corporate Criminal Enforcement Priorities

The Criminal Division’s plan is directed at “corporate crime in areas that will have the greatest impact in protecting American

citizens and companies and promoting U.S. interests,” and prioritizes 10 “high-impact areas” for investigative and

prosecutorial focus:

1. Fraud, waste, and abuse, including health care fraud and federal program and procurement fraud.

2. Trade and customs fraud, including tariff evasion.

3. Fraud perpetrated through special purpose vehicles or variable interest entities, including securities fraud and market

manipulation.

4. Fraud on U.S. investors, including through Ponzi schemes.

5. National security threats, including threats to the U.S. financial system.

6. Support to terrorist organizations, including designated cartels.

7. Complex money laundering.

8. Violations of the Controlled Substances Act and the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, including illegal distribution of

fentanyl and other drugs.

9. Bribery and associated money laundering.

10. Certain crimes involving digital assets.

In investigating and prosecuting these types of conduct, the Criminal Division further commits to prioritize “schemes involving

senior-level personnel or other culpable actors, demonstrable loss, and efforts to obstruct justice,” and the identification and

seizure of “assets that are the proceeds of, or involved in” such conduct.

Corporate Enforcement Policy Changes

The CEP was introduced in 2016 as a pilot program for the Criminal Division’s Foreign Corrupt Practices Act unit. In 2018, the

policy was extended to “all other corporate matters” handled by the Criminal Division. In 2023, the CEP was revised again to

further incentivize self-disclosure through greater fine discounts. But at the same time, DOJ leadership announced that

non-prosecution agreements (NPAs) and deferred prosecution agreements would be “disfavored” without fast and full

cooperation. (Alston & Bird’s analysis of the CEP changes over time appears in advisories, available here, here, and here).

While this latest CEP update provides more certainty for companies who self-report and credit for “near misses,” it may also

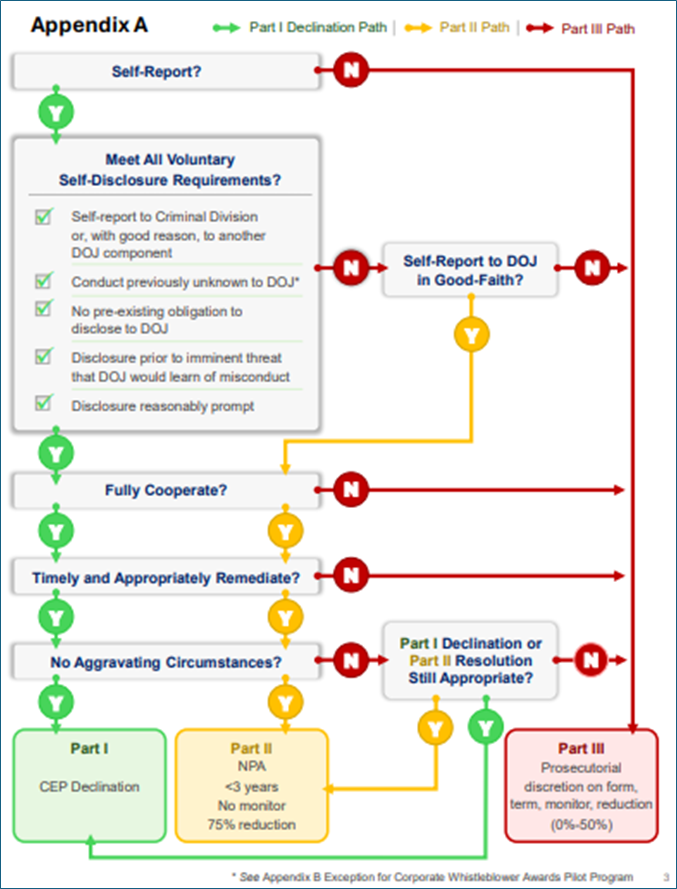

result in the DOJ wielding a bigger stick against companies deemed to fall outside that scope. The revised CEP offers three

categories of potential benefits for companies:

- To companies that (1) promptly and voluntarily self-disclose potential misconduct; (2) fully cooperate with the DOJ’s

investigation; and (3) undertake timely and appropriate remediation, the Criminal Division promises a declination of

enforcement action (provided no “aggravating circumstances” are present), rather than (as before) simply offering a

presumption of a declination. - To companies in the “near miss” category that do not qualify for a declination (due to failure to self-report or the presence

of aggravating circumstances), the Criminal Division promises an NPA with a term of 3 three years or less (except in

“exceedingly rare cases”), no monitor, and a 75% fine reduction (calculated from the low end of the applicable U.S.

Sentencing Guideline range). - To companies that fail to satisfy any of the three key criteria – voluntary self-disclosure, full cooperation, and timely and

appropriate remediation – the Criminal Division caps the available fine reduction at 50% (typically from the low end of the

applicable guideline range) and does not rule out the possibility of imposing an independent compliance monitor.

In an effort to further clarify these policy changes, the Criminal Division has, for the first time, distilled the CEP into a

flowchart:

Whistleblower Program Changes

To reinforce the changes to the CEP, Galeotti directed that the Criminal Division’s Corporate Whistleblower Awards Pilot

Program (covered in an earlier Alston & Bird advisory, available here) be amended to include six additional types of conduct

of interest. These new areas are:

1. Violations by corporations related to cartels and transnational criminal organizations, including money laundering.

2. Violations by corporations of federal immigration law.

3. Violations by corporations involving material support of terrorism.

4. Corporate sanctions offenses.

5. Corporate trade, tariff, and customs fraud.

6. Corporate procurement fraud.

Individuals reporting such conduct must still meet the Corporate Whistleblower Awards Pilot Program criteria. But the

program’s expansion increases corporate risk as companies continue to grapple with the significant implications of the

numerous whistleblower programs launched by the DOJ in 2024 (covered in an Alston & Bird advisory, available here).

Monitor Selection Policy Changes

In his Memorandum on the Selection of Monitors in Criminal Division Matters, Galeotti aims to “clarify[] the factors that

prosecutors must consider when determining whether a monitor is appropriate and how those factors should be applied” and

also emphasizes the need to “appropriately tailor and scope the monitor’s review and mandate.” To accomplish these goals,

the memo lists four criteria prosecutors are to consider when assessing the need for a monitor:

1. The risk of recurrence of criminal conduct that significantly impacts U.S. interests.

2. The availability and efficacy of other independent government oversight.

3. The efficacy of the company’s compliance program and culture of compliance at the time of the resolution.

4. The maturity of the company’s controls and its ability to independently test and update its compliance program.

Based on those criteria, if a prosecutor determines that a monitor is appropriate, then Galeotti’s memo requires prosecutors to

take three specific steps “to ensure [the monitorship] is carried out appropriately”:

1. Close scrutiny and management of costs associated with the monitorship, including a cap on hourly rates, a preliminary

budget, and periodically updated cost estimates.

2. Biannual (at least) “tri-partite” meetings of the government, the company, and the monitor to ensure alignment.

3. Ongoing collaboration among the government, the company, and the monitor, including “an open dialogue” among all

three parties.

This revised and restated DOJ approach to monitors largely mirrors that of the first Trump Administration, during which the

DOJ expressed greater hesitation to impose monitors as part of corporate criminal resolutions. In 2018, the DOJ issued a

memorandum from then Assistant Attorney General Brian Benczkowski (discussed in a prior Alston & Bird advisory, available

here), which instructed that monitors should only be imposed “where there is a demonstrated need for, and clear benefit to be

derived from, a monitorship relative to the projected costs and burdens.” Three years later, however, Biden Administration

Deputy Attorney General Lisa Monaco reversed course and signaled a greater DOJ appetite for the imposition of monitors

(see prior Alston & Bird analysis, available here). It appears the pendulum has now swung back again, with the Criminal

Division resuming something like its prior stance on monitorships and having already terminated certain existing monitorships

early.

Key Takeaways

White-collar enforcement remains a DOJ priority. Since President Trump’s reelection, speculation has swirled about

whether the DOJ would pull back from white-collar criminal enforcement. Various DOJ memoranda and Executive

Orders—most notably the President’s February 10, 2025 order purporting to “pause” DOJ enforcement of the Foreign

Corrupt Practices Act (discussed in a prior Alston & Bird advisory, available here)—have fueled such speculation and

uncertainty. But the Criminal Division’s new plan sends an unmistakable signal: DOJ white-collar enforcement will

continue, and may even expand, as clarified expectations and resource alignment take hold in the coming years.

Broad industry impact. The Criminal Division’s plan distills its white-collar enforcement focus into 10 “high-impact

areas,” which may at first seem to represent a narrowing of the Criminal Division’s focus. However, those areas span

multiple sectors, including health care and life sciences, financial services, investment management, industrials and

manufacturing, natural resources, defense, retail, and others.

The DOJ’s Criminal Division intends to flex its new muscles. Public reports indicate that DOJ leadership plans to

shift certain criminal enforcement responsibilities previously assigned to the Civil Division’s Consumer Protection Branch

to the Criminal Division, and the Criminal Division’s new plan appears to not only reflect that shift—by including as

priorities elder fraud, “fraud that threatens the health and safety of consumers,” and violations of the Food, Drug, and

Cosmetic Act—but to suggest that Criminal Division prosecutors will quickly put these reassigned authorities to use.

More opportunities for whistleblowers. The Criminal Division’s new plan indicates that any speculation that the DOJ

might scale back the Corporate Whistleblower Awards Pilot Program or otherwise express disinterest in whistleblowers is

unfounded. The new plan states that Criminal Division leadership has “reviewed the Criminal Division’s existing pilot

program” and made just one change: expanding the scope of conduct for which whistleblower reports will be

incentivized.

What does the DOJ’s commitment to “efficiency” mean in practice? Galeotti’s remarks in announcing the new

Criminal Division plan highlight potential concerns around DOJ white-collar enforcement: It can be costly, “unchecked,”

“unfocused,” and can drag on for years, unduly disrupting law-abiding businesses. The new plan commits the Criminal

Division to targeted, tailored white-collar enforcement and directs prosecutors to “move expeditiously to investigate

cases and make charging decisions.” But how this commitment will play out remains unclear—whether it will primarily

shape internal decision-making at the DOJ or lead to perceptible outward-facing changes such as more tailored DOJ

expectations and demands of cooperating companies.

A less patient DOJ? As welcome as this increased clarity and focus by the DOJ’s Criminal Division may be, the price of

it for companies likely will be some measure of diminished patience on the part of Criminal Division prosecutors and

supervisors regarding investigative or other delays by subjects and targets of investigations. This raises the stakes for

compliance improvements that will better ensure prompt detection of potentially illegal conduct, skilled and efficient

internal investigations of any such conduct, effective assessment of the all-important self-reporting decision, and adroit

engagement with the government.

Compliance ROI higher than ever. By returning to a more skeptical posture regarding the imposition of independent

compliance monitors, the Criminal Division is offering more of a potential reward than ever to companies that implement

robust compliance programs. Beyond preventing and detecting misconduct, such programs will position companies to

proactively engage with the DOJ and will better position companies to persuade a far more receptive DOJ that a monitor

is unnecessary.

_________________________________________

Originally published May 15, 2025.

Alston & Bird’s White Collar, Government & Internal Investigations team, which is composed of numerous former federal and

state prosecutors and agency staff (including several former DOJ Criminal Division prosecutors), will continue to monitor and

provide updates on the Criminal Division’s implementation of these new policies.

If you have any questions, or would like additional information, please contact one of the attorneys on our White Collar,

Government & Internal Investigations team.

You can subscribe to future advisories and other Alston & Bird publications by completing our publications subscription form.